Cody Bratt

Cody Bratt

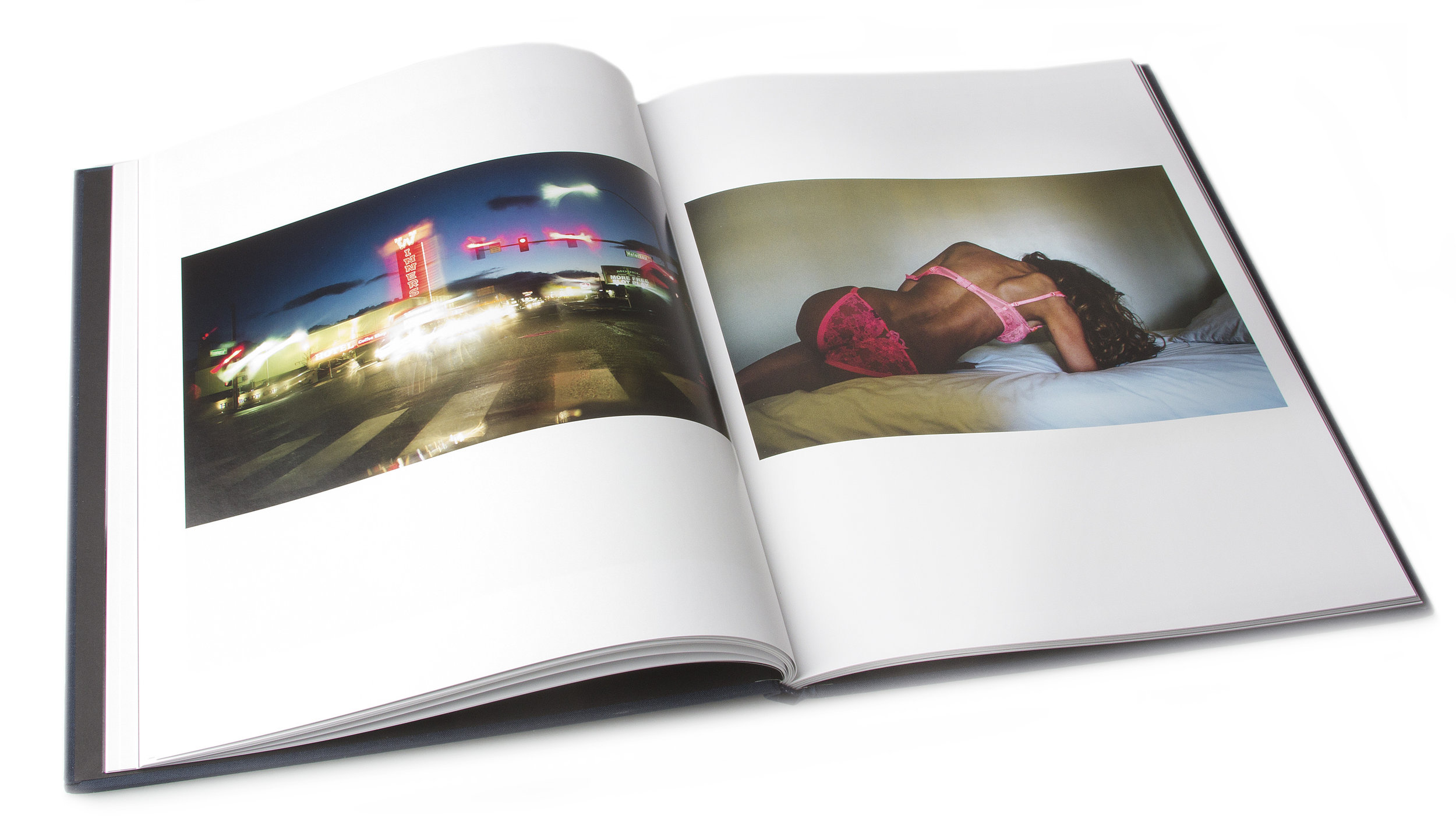

Love We Leave Behind

Hardcover

10 x 13 inches

96 pages / 56 images

2018

Fraction Editions

From the artist:

“Don't leave me now

Don't say goodbye

Don't turn around

Leave me high and dry

I hear the birds on the summer breeze, I drive fast

I am alone in the night

Been tryin' hard not to get in trouble, but I

I've got a war in my mind

I just ride

Just ride, I just ride, I just ride”

- Lyrics by Lana Del Rey, Ride

“Love We Leave Behind” is born from revisited memories of a formative relationship I shared with a partner many years ago. We loved each other fervently, yet we were unable to manage the respective fears and challenges we each brought to the other. As the relationship progressed, we were unaware that we were endlessly pirouetting between joy and self-destruction with each passing day. Even as we began to realize, neither of us were quite able to let go of each despite passing the relationship’s expiration date.

In making these photographs and the monograph, I wanted to create an “emotional documentary” of which depicts the journey one might take in trying to find the strength to break away from such a sickly love. Each photograph doesn’t mark a literal or specific memory. I mean the photographs to be read as an ambiguous state of mind, as memories and dreams simultaneously half invented and half lived. Indeed, many of these moments are drawn from recurring images I only vaguely remember now.

My goal was to create a series of photographs which felt specific enough to be familiar, yet open enough for the viewer to inhabit and fill in with their own story. I borrowed recognizable visual tableaus from the American road trip and mixed them with intimate portraits in temporary spaces meant to depict the interior moments of the journey. Combined, I hope they render the lyrical, although never reliably factual, sense of searching, discovery and loss inherent in letting go.

Grab a copy of the book here

Book review by Kelsey Sucena |

There exists a canon of photographers for whom the cross-country roadtrip comes as a rite of passage. In 2016 I found myself on one such road trip as a friend and I drove from New York to Seattle. It was a tumultuous time in our lives, marked by adolescent freedom and by political upheaval. I remember a night we spent in Seattle watching in shock as election results poured in. We woke the next morning to an America we had, in our privileged bubbles of art and academia, failed to imagine. Suddenly the neon glow of welcome signs lost their charm. America, we found, was a lonely place, subverted by the limits of our vision, and by a preoccupation with nostalgia.

The question of what to do with this loneliness has challenged photographers and artists ever since. For most the question has been ‘What do we take away from all of this?’ For Cody Bratt that question seems to be ‘what do we leave behind?’

I’ve spent the last few weeks with Bratts monograph wondering ‘what exactly draws me to these photographs?’ Neon motel signs, gas stations, rail cars. Such rich landscapes and beautiful people are not unfamiliar subjects, but they are tinged with an airy and uneasy atmosphere. They depict old and dead places, rendered in sharp detail, crisp color and dramatic composition. They sound like a Houndmouth song and read like a Kerouac novel, reflecting the work of monumental figures like Stephen Shore, while echoing the techniques of Todd Hido and Ryan Mcginley.

At first viewing, Love We Leave Behind (2018, Fraction Editions) appears to be a cinematic homage to the kinds of landscapes that have come to dominate our vision of classic Hollywood films. As I spend time within its space this first assessment starts to unravel. Soon I am struck by my own sense of longing. There may be a better word for it, but for now ‘nostalgia’ stands in as my placeholder. Whatever word might more closely approximate this feeling would also inevitably also shed light upon the appeal of phrases like “Great Again”, or the preponderance of rebooted film and television.

Beyond the places, Bratt offers us people. These people, mostly but not entirely women (gender is a subject he seems to be exploring), are noticeably young, and attractive. Most are rendered naked and sexual. They look as though they’ve sprung directly from a Tarantino film or a spread within the pages of Playboy. They are also weary, tired, exhausted and oppressed by the ruins which surrounds them.

Bratt tells us that his work is meant to explore his own uneasy experiences within a toxic relationship.

“In making these photographs and the monograph, I wanted to create an ‘emotional documentary’ of which depicts the journey one might take to find the strength to break away from such a sickly love.”

So then, sickly and toxic love is placed at the heart of Bratts project. He also tells us that, though the work explores his own experiences, it is not an exact document and therefore not constrained to the realm of honesty. Instead the photographer plays with reality, imbuing the work with a loose narrative through the use of fragmented sequencing. Here the theatrics of light and acting play out as we are given toxic loves in lieu of any one toxic lover.

This is a notable distinction in part because the fragmentation of our lover turned antagonist produces a sense of weightlessness as well as unfamiliar loss. Because we aren’t given any one person we’re forced to imagine each one as Bratts lover. This opens up space for us, the viewer, to imagine our own experiences, to project our own lost love into the sequence. It also works to situate us within the aftermath of a relationship, as when one explores shallow romances with many people in the wake of a desperate but deep love.

Because there are so many lovers I begin to imagine Kerouac's escapades. Kerouac wrote a chaotic life into the pages of On The Road. His was rife with the kind of toxicity that Bratt is trying to explore. Drugs, meaningless sex and masculine posturing push Kerouac's proxy, Sal Paradise, forward. Paradise, who refuses to settle in any one place, takes to nomadism and rebellion to rage against the contours of his rigid post-war society.

Its an alluring notion, that movement can offer freedom, but upon revisiting the text years after having read it the first time, Sal’s gestures reveal themselves to be empty. It is ironic but not surprising that the iconoclasts of the 50s and 60s have become the icons of today. So it goes with the dry-rot of nostalgia.

Kerouac is a good anchor for our exploration of Bratts photographs, if only because Kerouac's musings helped to define the America these photographs seem to crave. Indeed, Kerouac's preamble to Robert Frank's The Americans can be credited with helping to launch the very genre of photobook in which The Love We Leave Behind is contained.

As I sit with the book I find myself feeling lonely. Misty motels and rusty mountains give way to anxiety, fear, desire, confusion, the emotional trappings of brief but intense love affairs. I begin to wonder about the lovers. I imagine these pictures as having been taken immediately after Sal Paradise’s departure, in that empty space between the motel checkout and the crumbling pavement of the road. We are left to wonder about the emotional affect that these photographs have left upon the lovers. Do they crumble in the wake of glorious love, as these roadways and trailer parks do? Are they, like the landscape of route 66, left to rot? In leaving them, what has Bratt left behind?

In the same way that I am forced to reevaluate America, so I am forced to reconsider my love affair with these photographs. As I sit with them I start to see that they are not offering the same excitement of On The Road or The Americans so much as they offer a soft critique. And here is the brilliance of The Love We Leave Behind. In giving us these beautiful photographs, and framing them with the context of toxic love, Cody Bratt asks us to reevaluate our own expectations.

I think that our love affair with vintage Americana is coming to an end. As it shapes the lives of the lovers so too does the road shape our destiny. In learning to let it go, to abandon the nostalgia that blinds us to the rust of history, we may be able to liberate ourselves from the vicious cycles of culture that Kerouac perpetuated. Perhaps it is time to begin asking ourselves ‘how exactly, do these places effect us’? And how exactly can we learn to leave them behind?

Grab a copy of the book here